A tool for developing situated, joined-up views of people, institutions, and practices

With our T-lab 1, experts in the fields of arts and culture collaborated with practitioners in London to explore the potential of mapping for infrastructuring meaningful meanwhile activities. The result is a tool that describes the mapping process for academics/practitioners/others seeking to take a joined-up situated view of urban complexity.

Over the past decade, temporary urbanism has emerged in response to the global financial crisis and austerity. The temporary city is an urban model which promotes ephemerality and disruption, as opposed to continuity and permanence. It has been critiqued for alluding to alternative imagined futures without actually having any meaningful legacy, instead its temporariness acts as a distraction to bigger issues (Ferreri, 2021, p. 29). It can configure insecurity to appear positive, whilst consuming the space/time of practices that could be genuinely radical, disruptive or transformative (Harris, 2020).

In the midst of continued crises, more austerity, and post covid, UK cities are tired (Madden, 2022). The politics of urban exhaustion place new challenges on people, practitioners, and institutions. One of the key challenges faced at Euston, in London, whilst developing a portfolio of meanwhile projects, relates to how T-Factor can give space and time to practices that generate positive social impact; practices that are situated, radical and transformative. How can we ensure that the work we do is socially engaged? Without linking research and practice to specific sites, and existing local knowledge, there is a risk that meanwhile events lack meaning and can be misappropriated towards cynical gentrification processes, which, in turn increase urban precarity and inequality.

With an awareness of some of the urban complexity at Euston and a curiosity to find out more, T-Lab 1 started a mapping process in 2020. Central St Martins (CSM) is based at Granary Square in Kings Cross, London, and has a vibrant population of practitioners who specialise in socially engaged practices. In order to learn how CSM can be a better neighbour to a diverse, but exhausted, population waiting in the long shadow of the proposed HS2 station development, T-lab 1 initiated conversations with 30 practitioners across: art, curation, fashion, architecture, textiles, ceramics, product design, service design, and graphic design.

These conversations took the form of semi-structured interviews which covered; existing practices; situations; collaborations; purpose; timing; processes; measures of success; and potential connections to T-Factor. It was a form of asset mapping, which took into account resources, skills, interests and opportunities, with the aim of building a community of practice (Wenger, 1998), that could mobilise to the tangible benefit of people living in Euston.

In parallel with the conversations happening at CSM, the Knowledge Quarter (KQ) was funded by T-Factor to conduct a similar series of interviews with its members. The KQ is a consortium of partner organisations based in and around Kings Cross. They are made up of over 100 academic, cultural, research, scientific, and media organisations with a shared interest in advancing and sharing knowledge. These 25 interviews gave a comprehensive overview of what archives, museums, libraries, higher education institutions, charities, theatres, and performance groups were doing to connect locally.

T-Lab 1’s approach took influence from ‘infrastructuring’, which is a participatory design methodology that seeks to co-create enabling conditions for collaboration. It is a process-based approach typically developed in response to marginalised communities. It legitimises, organises and amplifies diverse viewpoints (Björgvinsson et al., 2012, p. 143) and can be described as a matchmaking process which takes place within an open-ended design structure without predefined goals or fixed timelines.

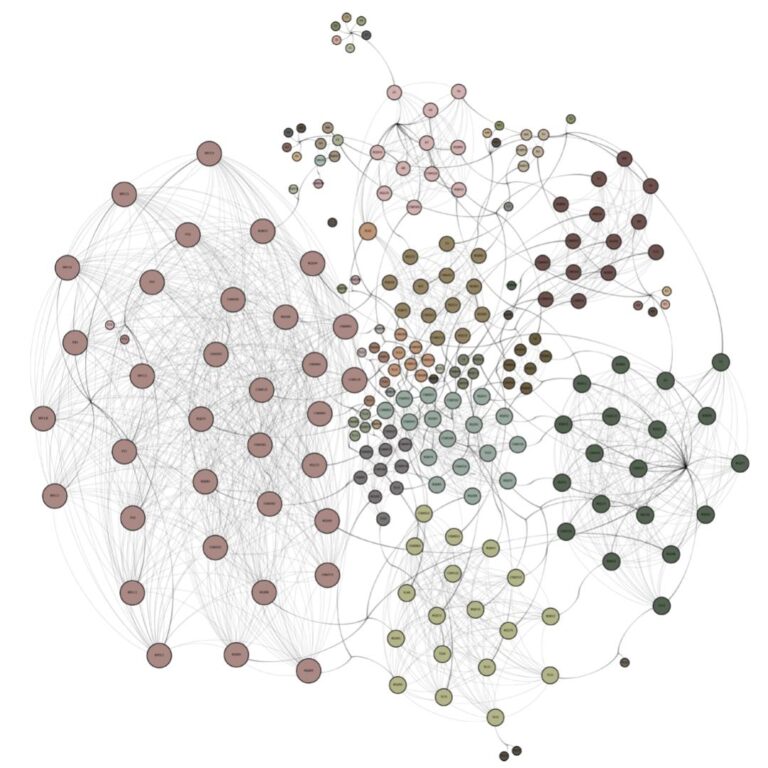

In order to facilitate closer alignment, and better matchmaking, the data from the CSM and KQ interviews were combined into a spreadsheet which recorded: interests; practices; locations; field; and missions. The interests and missions sections took reference from the T-Factor Activity plans and other pilot cities and T-labs were also added. In addition to this, data from the Regents Park Community Champions and the emergent community consultation around story gathering were also added. As such, information from across CSM, the KQ, and local knowledges and interests from Euston, were combined. This was then visualised using open-source network analysis software (Gephi). The resultant mapping gave a comprehensive joined-up overview of interests, aspirations, and practices, which helped T-lab 1 make decisions about where and how to act.

The mapping showed clusters of people, organisations, and practitioners, who shared common interest in activities such as: story gathering; engagement; knowledge and skill exchange; situated practices; and local resources, skills and assets. By arranging things in relation to interests, a level field was created, which broke down disciplinary, institutional and sectoral silos. The visualisation sought to legitimise and organise the diverse interests of the group in preparation for the next phases of T-factor. With a better understanding of the specific interests, aspirations and assets at Euston, T-lab 1 is in a strong position to facilitate matchmaking and closer alignment towards situated, radical and transformative practices that are meaningfully linked with specific sites and publics, in the hope that T-Factor’s legacy at Euston is one of improved urban equality.

KEY LEARNINGS

- By starting the process through talking to people and gathering information on an interview canvas we were able to develop an overview of diverse skills, interests and opportunities.

- Projects like T-Factor can seem big and impenetrable to external parties, so there is value in talking 1:1 with potential collaborators and framing the activities as emergent and responsive, rather than predetermined.

- In complex situations, it can be difficult to see things in joined-up ways, visualisation of the data allows us to find new connections that might otherwise have been missed.

- The activities evolved in response to the on-the-ground activities of the pilot, as such there was a need to be open and agile. For example, the largest cluster on the mapping ‘story gathering’ came last, but its inclusion was vital, as it was co-produced with residents and charities.

Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P.-A. (2012). Agonistic participatory design: working with marginalised social movements. CoDesign, 8(2-3), 127-144.

Ferreri, M. (2021). The Permanence of Temporary Urbanism: Normalising Precarity in Austerity London. Amsterdam University Press. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CP4LzgEACAAJ

Harris, E. (2020). Rebranding Precarity: Pop-up Culture as the Seductive New Normal. Zed Books. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=3pv9DwAAQBAJ

Madden, D. (2022). Tired city: on the politics of urban exhaustion. City, 26(4), 559-561. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2084264

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511803932