Marta Arniani – Futuribile, Wild Spots.

Things are set in motion on a grey and windy February morning in Amsterdam, one of those that feel like a major force stole half of the colour palette of the world, and you are left there with a heavy sky pressing on your shoulders. The location is a small pond on the side of Amsterdam University College’s main building: it is surrounded by small patches of grass, two bare trees and concrete steps forming a sort of arena. I remember thinking, “we will need a grandiose dose of imagination here”. But that was precisely what it was all about. In the coming months, together with a group of students from the Anthropologies of Community course by Professor Scott Dalby and colleagues from the T-Factor project, we would have turned that neglected pond area into the first-ever Wild Spot.

The Wild Spot is a place that exists in time and space, but besides the presence of nature, more than its physical properties what makes a Wild Spot is the experiential learning and community process leading to it. The Wild Spot is an ecological placemaking project that anchors personal, community and planetary wellbeing in place-based nature connectedness. Acknowledging that attention is crucial in world-making, it aims to re-educate participants’ attention towards ecology, community and self-awareness. Throughout the process, a local green area becomes a “Wild Spot”, a hotspot to disconnect from the cognitive fatigue of the information economy and reconnect with nature, oneself and the others.

Curatorial statement

The Wild Spot – now also a non-profit organisation – is the evolution of my independent research on technology’s role in cities, which is progressively moving away from a critique of technosolutionism towards developing means and methodologies to restore some of its collateral damages. With the Wild Spot, I wanted to explore how individual and collective training of attention through nature-connectedness activities can be a resource to face complex planetary challenges. Indeed, attention is crucial in world-making, and if, on one side, scientists like Robert Michael Pyle started long ago to state that the disconnection from nature in our everyday is a significant element of the climate crisis, on the other, from the Snowden revelations and the Cambridge Analytica scandal we are also well warned of the impact of the attention economy in polarising the public opinion, creating new dopamine addictions and distorting reality. Hence, the Wild Spot is a way to propose accessible methodologies and strategies anchored in nature connectedness to re-educate attention from the unaware use of screens towards ecology and community. Nature connectedness can indeed help in three spheres:

- Developing biophilia and understanding how all beings are constantly in a web of relations beyond anthropocentrism.

- Improving mental, physical and social well-being of individuals and communities.

- Emancipating attention from the ubiquitous regime of surveillance and distractions fuelled by the digital economy.

From a conceptual point of view, the Wild Spot is anchored in different disciplines. The first is temporary urbanism, as framed in T-Factor Time Manifesto, as a resource to accelerate just transition in European cities: bottom-up trials can go beyond short-termism and “complement macro investments in climate adaptation, mitigation and resilience” in an inclusive way.

In the Wild Spot, temporary urbanism, enacted in the community repurposing of a green area, is a means to build a culture (intended as knowledge and habits) around nature and planetary well-being. It also promotes a deep ecology gaze towards nature that acknowledges its inherent value beyond its usefulness for human beings. This cultural approach ties identity and belonging to local green spaces. As biologist and climate educator Spencer Scott puts it, we must become “people of place”. If everything in our global and dislocated society creates distance between production, individuals and extreme climate events, tethering oneself to a place and a community is a “reinforcing framework for climate-positive behaviour”. Pro-environmental behaviours are also developed instinctively through what psychology defines as nature-connectedness, the “measure of an individual’s trait levels of feeling emotionally connected to the natural world” (Mayer and Frantz, 2004).

A growing body of medical research states that connection with nature has several positive impacts on mental and physical well-being, such as strengthening the immune system, reducing the stress hormone cortisol, enhancing cardiovascular and mental health, and restoring cognitive attention. The latter, attention restoration, refers to the ability of nature to refill our direct attention capabilities by nurturing our indirect attention. This quality is particularly relevant in the Wild Spot missions of re-educating attention and providing an interruption of the “smart” city. In the digitalisation of every wake of life, our attention becomes an atrophied muscle caught in an endless cycle of dopamine releases chasing. As philosopher André Citton puts it, attention is one of the scarcest goods in the attention economy and also a potent tool to refund politics through the reappropriation of individual and collective awareness, which creates the “attention regime” behind the global vision, values and mechanisms making our world what it is.

The project also calls on the politics and sociology of technology and participatory art to provide a symbolic interruption of the smart city. The contemporary debate about surveillance in public spaces around the EU AI act show how the ubiquitous digital landscape is a technical layer that technology providers had a large margin to widespread and embed in every wake of human activity before being put under public scrutiny. There is evidence that the policy making discourse on surveillance evolved in the past fifty years, making acceptable, for the sake of optimisation, activities like cross-border data gathering that were previously considered dangerous for democracy.

Citizens don’t signal their consensus to be filmed when they enter a public space: if well-developed online, the notion of privacy in physical space, or “ambient privacy” (Maciej Ceglowski), is still in its infancy. Hence, the Wild Spot enacts also symbolically the “possibility to disappear” that wilderness grants us. The “wild” of the Wild Spot refers to this figurative remoteness, which in our society is romanticised and marketed in any possible way, but with the idea to offer a glimpse into it in an urban garden: locally, for free and without long course transport emissions. The wild also stands for all the natural elements and ancestral wisdom erased or colonised by Western culture separation between the mind and the body.

Moving from these scientific and research bases, The Wild Spot is an ecological placemaking project that anchors personal, community and planetary well-being in place-based nature connectedness.

What makes a community?

Community is not a universal concept but evolves across cultures, places and time. In the Anthropologies of Community course, professor Scott Dalby deconstructs the academic idea of community, a simple and local organisation built as bucolic opposition to the industrial foundation and the complexity of society. Its syllabus dwells on deep ecology, shamanism, decolonisation practices, indigenous knowledge and post-humanism. With Prof. Dalby, we have found a meeting ground in nature, embodiment and perception as learning and self-awareness tools. We integrated the Wild Spot curricula into the course and proposed it to students as a means to put the theoretical approaches presented into practice.

On that cold February day, most of the students put their foot for the first time in the Wild Spot site, which until that moment was considered by many a “no man’s land”, and tried first-hand some techniques to ground in nature.

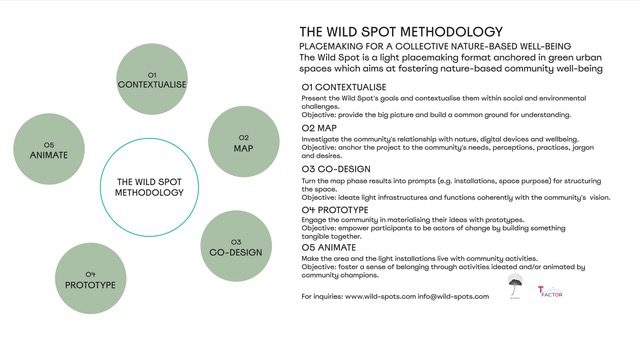

The Wild Spot methodology consisted of encounters with the students culminating in a showcase during the local landscape festival “Met Andere Ogen” (“with other eyes”) organised over the following Summer by T-Factor partner Waag. The process can be divided into the next main phases:

- Contextualise: Present the Wild Spot’s goals and contextualise them within social and environmental challenges. Objective: provide the big picture and build a common ground for understanding.

- Map: Investigate the community’s relationship with nature, digital devices and wellbeing. Objective: anchor the project to the community’s needs, perceptions, practices, jargon and desires.

- Co-design: Turn the map phase results into prompts (e.g. installations, space purpose) for structuring the space. Objective: ideate light infrastructures and functions coherently with the community’s vision.

- Prototype: Engage the community in materialising their ideas with prototypes. Objective: empower participants to be actors of change by building something tangible together.

- Animation: Make the area and the light installations live with community activities. Objective: foster a sense of belonging through activities ideated and/or animated by community champions.

The festival saw the presentation of the project from the perspective of its creator Marta Arniani, Prof. Scott Dalby, as community expert, educator and tutor interfacing daily with students’ well-being, and a representation of ‘activator’ students. The T-talk (how we dub knowledge-sharing panels in T-Factor) was followed by a visit to the Wild Spot and an activity animated by students for the festival dwellers. Colleagues from Aalborg University and Land intervened respectively in the mapping and co-design phases, bringing in expertise on data mapping and landscape design, while pilot coordinator Waag supported the facilitation and local implementation of the project.

The project methodology is grounded in participatory design, which is anchored in including and giving an active role in addressing a challenge to the stakeholders directly interfacing with it. The methodology included recent developments in animal-aided design and inclusive design.

Outcomes and Impacts

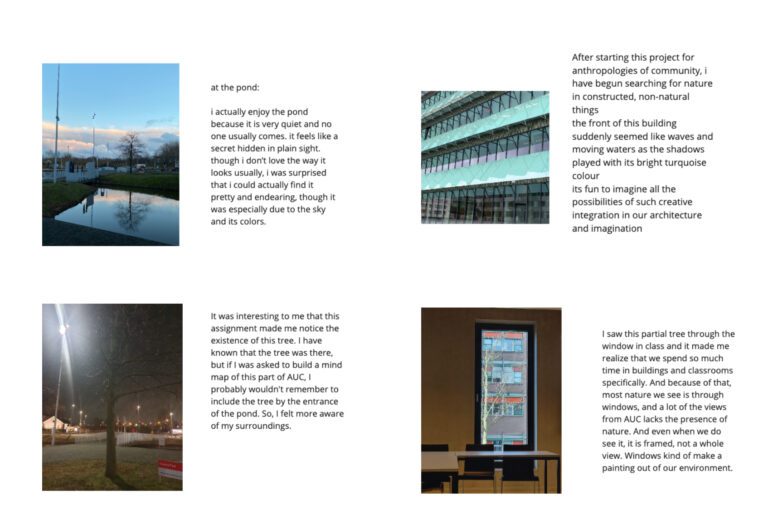

On the data collection side, the process resulted in a collective nature observation journal that students kept over two weeks, monitoring of their relationship with technology, a catalogue of their wellbeing practices, a mapping of the everyday stressors, and a wish list from both the classroom and other students about how to use the Wild Spot area. The glimpse of students’ life emerging from the progress calls for a larger taking charge of wellbeing at the campus: intense academic deadlines and workload, mobile addiction, economic precariousness and a whole palette of anxieties and stress accompany their everyday. There is a high degree of self-consciousness: “phone use time increases when my mental health decreases or when I am more overwhelmed”, “I am not getting enough sleep”, “I have been feeling very anxious past few days, relating to upcoming assignments and things I have to do”. When it comes to wellbeing practices, a large part of the students expressed a need for activities involving the senses and the body, like cooking, dancing, walking in nature and recharging in the sun. The Wild Spot can tap into their needs and consciousness and creating a safe place for expression and wellbeing.

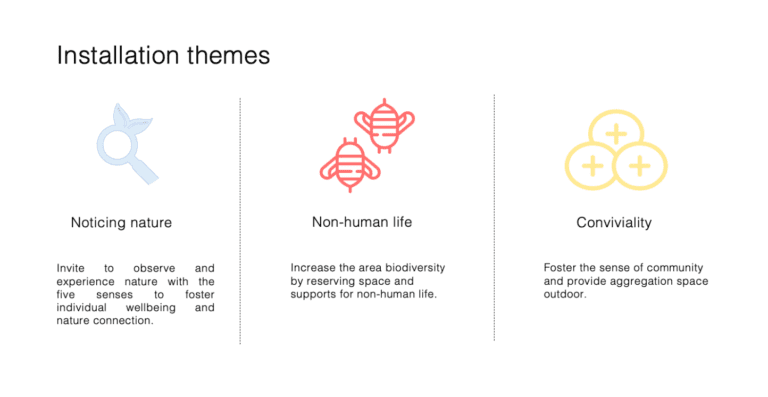

The co-design and production steps led to the proposal of 12 installations categorised into three areas: noticing nature, for non-humans and conviviality. Ideas ranged from a “reclination station” to disappear in the grass and observe the sky to a community materials box with cushions and towels, a vertical garden with edible plants, bird houses and insect hotels, motivational way-finding and extra steps to make the arena area more accessible.

Impacts can be categorised into ecological, social and on the masterplan level.

Social impacts

- Empower students to be actors of change in their everyday and on campus

- Foster community building and well-being centred on nature

- Educate about the well-being effects of nature and how to integrate them into everyday life

- Raise awareness about the health and social externalities of the digital landscape

- Create a safe space for discussion to break taboos on what are considered “vulnerabilities” in society, such as anxiety, depression, fear of missing out, financial insecurity

- Provide a next-door and free means to soothe stress and anxiety

- Create a material safe place for collective care practices, where individual well-being strategies can be turned into collective ones

Masterplan impacts

- Contribute to the local landscape festival and the ecological mission of the pilot with an experiential learning methodology that transformed one area of Amsterdam Science Park

- Create a project that can live over time (activated by today’s students and inherited by future ones)

- Open up the possibility for new meanings and employment for a so far under-used area of the campus

- Build a safe and evidence-based common ground for dialogue between the institution and the students

Ecological impacts

- Non-human & nature conservation practices embedded in design

- Area favouring nature noticing & change of perspective

- Intentional low footprint (of human activities not consuming or producing data and of the installations)

- Creation of zones reserved for non-humans

- Test a rewilding of some parts of the area

A resilient future is not only a matter of infrastructures

To increase their resilience to the climate crisis, cities worldwide are embedding nature-based solutions in the urban infrastructure, for instance, increasing the concentration of trees to lower temperatures and support biodiversity, deploying systems to recycle rainwater or augmenting the number of cyclable lanes. All these laudable initiatives are technical measures, which do not per se guarantee the large-scale behavioural change towards more sustainable lifestyles essential to a just transition. Indeed, science tells us that developing nature connectedness is fundamental to developing enduring pro-environmental behaviours. This is done more effectively through emotional bonds and first-hand somatic experience of nature’s well-being effects. Nonetheless, besides providing information that stops at the cognitive level, Europe has yet to have a concrete plan to educate its urban citizens towards nature connectedness. This is where the Wild Spot can make a difference as an experiential learning curriculum.

The Wild Spot is indeed a process to address locally, in an experiential, collective and tangible way, global challenges that can be easily disempowering for individuals and communities. Against fundamentally systemic changes evolving in ways we struggle to understand and predict, we are often trapped in paradigms of responsible behaviours as individual duty. Local resilience can be a resource. The principal novelty of the project lies in creating a connection between two major societal challenges: the climate crisis and the technology race.

Looking at the environmental and societal externalities of both can be a disempowering awareness-raising exercise: loss of biodiversity, population displacement, exploitation of populations and natural resources to build components, data centres pollution, surveillance normalisation, social fragmentation, loss of fundamental human rights, automated discrimination… Who wants to live in such a world? Through the lens of well-being, described holistically as a state of health at the physical, mental, social, spiritual and planetary level, the Wild Spot creates an empowering process around the role and the habits each citizen, starting from their attention, can adopt in their local every day to be actors of change.